Who Made Caitlin Clark A Good White Girl?

This article was originally published on Flaming Hydra on July 2. If you like it, we encourage you to visit their site and subscribe.

It was something like five years before she was born that the moral panic over Caitlin Clark began. This was 1997, the year the WNBA debuted. The NBA was bleeding from the teeth to lock out its workers. Culture war was in the air, and the country hovered uneasily at sports pundit DEFCON 2. Mike Lupica was doing so much heavy breathing, the whole tri-state area could’ve told you what he’d had for lunch on any given day. A racist demonology, never far from any conversation about basketball, was being summoned to the breach between the owners and the players. The NBA had been overrun with greedy thugs, it was felt in certain quarters, and the time had come to bring them to heel.

And now here came the WNBA, the respectable alternative, “the good apple in the increasingly rotting barrel of professional sports,” as Newsweek put it. This was real basketball, uncorrupted by all that blinged-out commerce, dedicated to “fundamental” play. A year earlier, John Wooden, the former UCLA coach, had declared the women’s game the “best pure basketball” around, decrying the “showmanship” of the men’s game and calling as he often did for a ban on dunking, as if there were something shameful about watching people fly. Lest you imagine this sort of sniffing was restricted to tedious old Rotarian cranks, even Ann Meyers, a real hooper’s hooper in her day, was singing from the same hymnal:

The women’s edge is they do the fundamentals. It’s a great game. The men’s game has gotten out of hand a little bit. They carry the ball, they travel. They’ve gotten away from fundamentals. The taunting, the fights, the trash talking. I don’t think there’s any place for it in the game.

Thus was the WNBA sold by the NBA’s own marketers. It would be everything that Allen Iverson and Kevin Garnett were not—“the anti-NBA,” Newsweek called it. Because WNBA rules required players to be at least 22 years old or to have exhausted their college eligibility, the league would suffer none of “the foolishness and egos of young millionaires just out of high school,” in the magazine’s phrase. Of the foolishness and egos of the old billionaires actually in charge, Newsweek had nothing to say.

Even back then, there was no mystery about what the new league was up to. The WNBA was seeking to legitimate itself by way of an explicit appeal to respectability—specifically, white, bourgeois respectability. NBA players may have, as The New Republic lamented of Latrell Sprewell, “leapfrogged…middle class values”—oh fucking eat me, Marty Peretz—but the WNBA was here to uphold those values and serve as their faithful custodian.

Purity. Fundamentals. Class. Over and over you heard the same themes. “Classy would become the operative word used to describe the image of the USA Basketball women’s national team,” Sara Corbett wrote of the ‘96 Olympics squad, whose romp through Atlanta that summer was a sort of test run for the WNBA. Corbett described a compulsory day of media training at training camp, during which the players “were instructed on how to be classy athletes”:

Classy meant several things. It meant that in talking to the media, you used complete sentences. It meant you smiled even if you felt put upon or tired or sick of getting asked the same silly questions. You smiled if you won, and you especially smiled if you lost, since pouting did not qualify as classy. You never trashed your teammates or your coach or anyone else for that matter, but most important, since the reporters would be fishing for it, you never trashed your opponents. If you imagined your opponents would beat you, you spoke highly of them. If you knew they were nothing more than meat for your grinder, you spoke extra highly of them so as not to appear cocky, which, like pouting, was not classy.

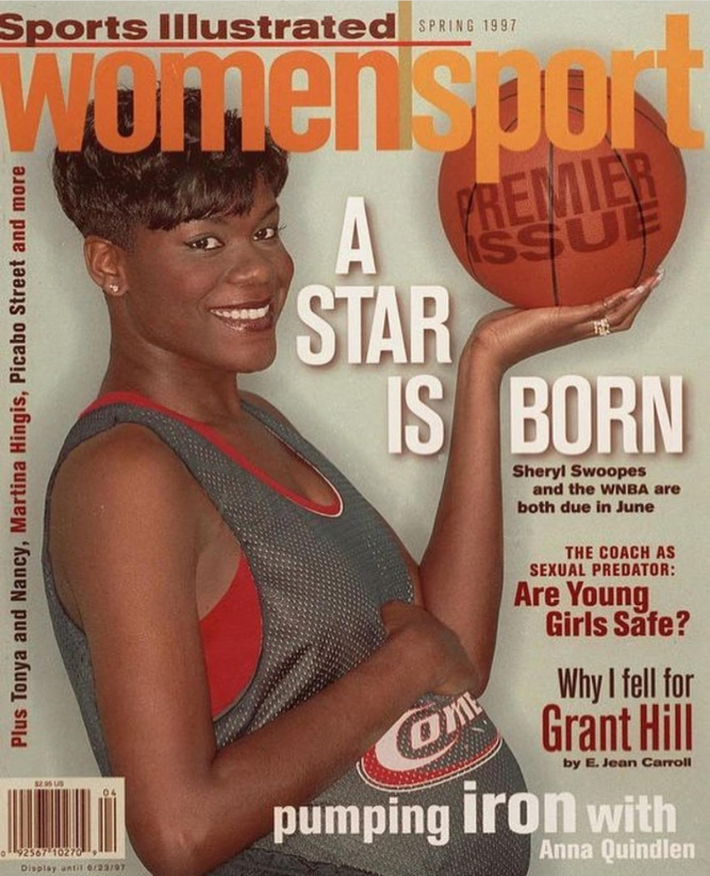

They were being drilled in the dramaturgy of normie reassurance, in other words, pantomiming for some imagined audience their abstention from a certain set of deviant behaviors. The stars of this particular show, at least in the early days of the WNBA, were the moms. The young league was fat with stories about women who happily balanced motherhood and hoops. Around the time the young Black son of an NBA player was toddling onto the cover of Sports Illustrated beneath the question, “WHERE’S DADDY?,” Rick Welts, the chief marketing officer for the NBA and WNBA, was saying of the women’s league, “We embrace maternity.” (Though not quite all maternity; just ask Dearica Hamby.)

A favorite of WNBA media in those initial seasons was Suzie McConnell-Serio, a point guard for the now-defunct Cleveland Rockers, owner of one of those bobbing blond ponytails that bedecked the league like pennants outside a grand opening.

“The season is short, but that will grow and grow and with that, so will salaries, but I don’t know how much [the lifestyle] would change,” she told a reporter. “I know I would still be the same ol’ Suzie McConnell-Serio, mother of four, wife.” She told the Lifetime network, a WNBA broadcaster in those days, that “being a mother is the best job in the world.”

McConnell-Serio, in the deft reading of Mary G. McDonald, was the paradigmatic Good White Girl, a figure of “sincerity, concern, and nurturance.” The point of the Good White Girl was to distance the WNBA from any whiff of “excessive masculinity,” which also meant, given the invidious contrast the league was drawing with the NBA, any whiff of excessive Blackness.

In all a bargain was being struck, and it made for some knotty identity politics. The women would get their due as jocks—but on the condition that they renounce the Black idioms of their sport. They would get their shine as celebrities in their own right—just so long as they took care to reassure the public that they were “womanly,” within the narrowly defined parameters of the word. These were the basic terms underwriting the WNBA’s public image from the start. If over the years the players have, by their own agitation, wrought significant changes in how the league presents itself, there is still, at the center of everything, ponytail bobbing along, the Good White Girl.

Today, a straight white woman is the most beloved athlete in a professional sport long at pains to suppress that it was neither white nor all that straight. It’s Caitlin Clark’s blessing and curse to be so much of what the WNBA has always praised, and just enough of what it has damned: a Good White Girl, outwardly respectable, but with a game full of that fantastic blasphemy that sent John Wooden and Ann Meyers to their fainting couches—the taunting and trash-talking and showmanship.

She became a superstar in the first place by doing the things superstars do: shredding the college record book, not just beating but also fully demoralizing opponents all by herself, burying shots from distances somewhere between rude and hallucinatory. There were many reasons so many people tuned in to watch her play NCAA basketball, but underneath it all was the fact that they were more or less guaranteed to see her do something that lived up to the hype. She was another Larry Bird, down to the Midwestern origins, a swaggering cornpone hero to people who like to complain about swagger. This made her a phenomenon. It also put her in the odd position of being at once celebrated by the worst sort of fans and targeted by many of her peers.

And she is being targeted. We should be clear-eyed about that much. The reactionaries who’ve rushed to Clark’s side, perceiving the dread hand of wokeness in the various slights against her, are closer to the nerve of the matter than the well-meaning WNBA adherents who insist she’s only getting hazed like any heralded rookie. Even granting that the WNBA, as a small league with monopoly power and scarce roster space, is a rougher environment than most, it takes some effort not to see a pointed message in the cheap shots that have come Clark’s way, the hard screens and outright headhunting. The conservative panic, in all its chauvinism, points us toward the real cultural politics in play; the liberal dismissal, in all its right-mindedness, obscures them.

Yet the league partisans are correct in their impulse to identify something normal, something structural to the WNBA working itself out here. What’s happening is a kind of class polarization among the players. Clark’s celebrity is now the terrain on which her colleagues have mounted a resistance to the league’s respectability regime—to the very idea of the Good White Girl, which was always above all a means of differentiating and therefore controlling the workforce, the WNBA’s answer to the NBA’s Greedy Thug. This goes some way toward explaining, for instance, the loose campaign afoot in the media and even among her fellow players to pressure Clark into disavowing the bad parts of her fandom. It is an effort to enlist her in the project of refusing, as Paige Bueckers did a couple years ago, the shitty dividend paid out to the women who conform to Good White Girlhood.

“With the light that I have now as a white woman who leads a Black-led sport and celebrated here, I want to shed a light on Black women,” Bueckers said in her ESPYs acceptance speech. “They don’t get the media coverage that they deserve.”

Clark might join that cause, too, one day. Until then, her fame will be fought over, and its premises challenged; it will continue to be, to borrow an old line, the modality in which class gets lived in the WNBA. No more Good White Girls. Proles got next.

This article was originally published on Flaming Hydra on July 2. If you like it, we encourage you to visit their site and subscribe.