Giri Nathan DISHES On Jannik Sinner And Carlos Alcaraz In This EXCLUSIVE Interview

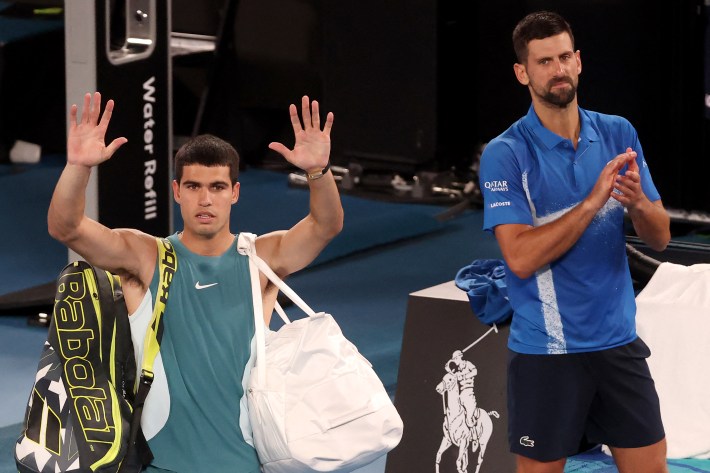

Defector’s own Giri Nathan is the father of an insanely great new baby and the author of an insanely great new book. Just as babies transform and master skills at alarming speed, so too have the young tennis prodigies at the center of his book. Changeover: A Young Rivalry and a New Era of Men’s Tennis, out today, is an account of the 2024 men’s tennis season, when the sport was finally captured by the steely, red-headed Jannik Sinner and by Carlos Alcaraz, the instinctive Spaniard. While he perfects his sleek and unassuming brand of tennis, Sinner’s season is clouded by a doping violation made public before the U.S. Open. The gregarious Alcaraz is a freakishly adept learner, shapeshifting on whatever surface, if more slowly adjusting to the emotional tumult of life on the tour.

Fans of Giri’s tennis writing will know exactly what pleasures await them: stylish turns of phrase, vivid description, and frequent laughs. In his Wimbledon quarterfinal, Sinner’s face looks “flattened and slack, like a pillowcase emptied of its pillow.” Alcaraz arrives at the tournament having studied old videos of himself for inspiration: “Tennis’s most brilliant pupil had decided he didn’t need a syllabus anymore; he had become his own assigned reading.” Giri writes about the two lads with a certain knowing affection, and a reader will feel totally at ease as he shows you around the colorful contemporary tennis world, trust he’s won through years of studying and covering the sport.

The timing of Defector’s annual staff retreat worked out so that I could congratulate Giri on both book and baby in-person last week. Sitting outside a suspect 24-hour hotel coffee shop called Java Beach, we spoke about the challenges of covering two rising stars and the art of sportswriting. The interview has been edited for clarity and length—sort of. It’s honestly still pretty long.

This is our first in-person Defector Writes A Book author interview, so congratulations on that honor.

Thank you.

In the most literal sense, the book is about something that already happened: the 2024 men’s tennis season—the actual “changeover” from Big Three winners to Alcaraz and Sinner splitting the Slams that year. But the book itself is also this argument for the significance of the change, that the future will be defined by the two of them. You have to kind of call your shot there, not that I think it was a particularly outlandish or risky conclusion. But I wonder how you approached those two big challenges of sportswriting: reproducing the immediacy of something that’s already happened while also trying to maintain some perspective when you’re still inside of a moment.

Those two things are kind of in tension with each other, right? I remember having this challenge even in the moment when I was trying to explain Carlos Alcaraz’s rise, because it struck me as historically significant—just his talent on the court—but also I wanted to have a sense of perspective and not get too carried away with it, because I had hyped up plenty of false-messiah players in the past and I didn’t want to get caught again. So I think those things are always in tension. How do you do something justice in terms of how special—and in the case of these two players, how talented—they are, but also couch it in a historical context?

There’s often this panic among the tennis commentariat. As soon as they thought the Big Three were fading out, and there were a couple of false alarms on this, they were like, “Oh my god, what could possibly come next? What could be nearly as good as this?” Part of what I wanted to do in the book is assuage that panic. There’s always talented people at any given domain of sports or human activity. There’s always going to be something cool to pay attention to, and I’m choosing to zero in on this season because it seems fairly obvious that they’re going to be the ones to follow for the decade ahead, but also I think it’ll be fun to capture, as kind of a time capsule, what it was like to watch them rise in the beginning.

And even after you started the book, there ended up being more intrigue in that one season, like the doping thing. Aside from the actual results themselves, what about the year or the two of them ended up surprising you, as someone who’d watched them pretty closely before?

Something about Jannik that was interesting is catching him in some more unguarded moments. He actually just seemed like a good hang. I don’t think he comes off that way in a lot of his public-facing stuff. I really got the sense that this is a guy who sort of resents the part of his job that’s having to do all the meet-and-greets, the influencer-ification of a modern-day athlete. I don’t think he’s into that. But it was cool to see those few moments where you could get an unguarded reply to a question and he would reflect on his own life. I thought he was pretty chill and insightful, and not nearly as mechanical as he sometimes seems on TV.

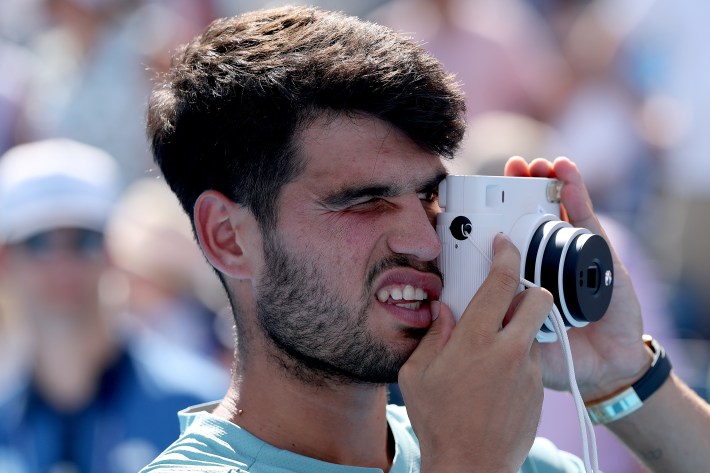

With Carlos, one interesting thing was he really does turn it on a lot. You wonder what he’s like in these more mundane moments of his life, but then I went to this thing he was doing for a sponsor and I see him walking around in a hallway, chatting up random people. I do feel like there’s a unified theory of Carlos that is accurate, where he actually is just this fun-loving, extremely gregarious and extroverted guy. I was hoping to complicate this picture, but I have no evidence to the contrary. This dude is so happy. I’ve seen him in a room of really annoying fans trying to get a piece of him, trying to get a selfie with him, and he’s just super patient and sunny. It’s like both faces of that same new superstardom, where one guy is kind of grumbling that he has to do this stuff and for another guy, it seems to really serve his personality. He was born at the exact right time. He was the superstar for these circumstances. I think that’s true in a lot of ways.

I also think it’s not an accident that he’s in this generation that grew up with the highlight reel as their basic unit of sports consumption. He talks a lot about how he’s on the court and he just wants to delight the people watching him. I can almost see it running across his eyes in the middle of playing, like Oh, I could do this shit and it would be on Instagram reels or TikTok later. He’s very much a creature of the moment.

The most out-and-out surprising thing both of them did in the season was have a major doping violation and smash his racquet. Kind of complicating this super happy-go-lucky personality, but those are obviously very different degrees of deviation from normal life. I tried to capture both of those: big scandal and mini scandal, respectively. Those are the biggest plot twists of the season. And they happened in the same week, which is kind of fun.

There’s a technique you use a lot, very effectively in this book, but also generally in your reported work, which is the sort of “third-party scouting report,” where you ask one player about another. I think of your hallway-length conversation with Roger Federer about Stefanos Tsitsipas. In this book, it helps situate Alcaraz and Sinner in this broader world, right? Both as part of some lineage, but also in the contemporary tapestry of men’s tennis. What are you looking for you when you ask players about each other?

In an ideal world, with an ideal conversation partner, like Daniil Medvedev, I’m looking for a super honest reflection about what sucks or what’s difficult about playing that player. You get 90 percent of the way just watching on TV, like what’s this person doing so well? But being on the other side of it, having to hit the ball that Carlos Alcaraz hits a hundred miles an hour—I think Medvedev can get very granular about how that hampers his technique or makes him second guess his shot selection. I’m looking for those moments of doubt. I think doubt is one of the most interesting things to write about with professional athletes, because their job requires delusional self-confidence. So usually when I’m asking them to reflect on other players, it’s like: How does this player crack or make you doubt your own game? And they’re often very willing to do that, even if it’s after fresh defeat.

Separately, you’ll also get them to comment on why that player’s unique in the context of the modern tour or recent history of the tour. Players love doing that with Carlos, in particular. I think they’re a little more restrained in their praise of Jannik. You get to see what they assign prestige to in their model of tennis. They see Carlos, and he’s hitting shots they couldn’t even dream of hitting. And then with Jannik, the praise is more like, Maybe if I just trained like he does, I could be that consistent and that technically sound. You don’t have the out-and-out awe as often. I like learning what their internal value system is, and that’s displayed through some of their comments, too.

Medvedev, I thought, was a really endearing figure in this book, which this longtime Medvedev truther appreciated. Who were some of your favorite non-Alcaraz, non-Sinner people to write?

It was definitely important for me to convey Medvedev because I think he’s this tragicomic figure, and he’s just a really good talker, too, so as much of his quotes and his antics as I could get into the book, I wanted to. He’s situated in an interesting place in the game’s history where he’s pinned between these two great cohorts of players, with the Big Three on one side and the next two guys on the other side, and he was able to sneak in his one major title in between, and maybe he’s got more to come, but he’s already such a good commentator around the game. Having him be an observer of this one era going and this next era coming, I thought, was really compelling.

Then there’s Djokovic, who’s a more spectral figure in the book. To the extent that he’s “in decline,” he’s in an interesting stage of an athlete’s life to write about. How did you approach him?

One thing I was talking about with my editor is that some of the sports books at the end of a player’s career are too reverent and sand away the eccentricities of a player. I think that’s definitely going to be the case with Novak, and I want to capture some of the real-time zaniness of following this incredible athlete.

What’s even left if you sand away his eccentricities?

I know, right? Just a really proud Serbian and family man. You could tell a really distorted story of Novak Djokovic as this graceful, gracious, great champion. But I think it’s a lot more fun to get into the weeds of what a colorful and odd character he is. One of my big goals in the book was to faithfully trap in amber the fan perceptions and general culture of the sport in this time, because I know it all gets distorted in retrospect. That’s true of Djokovic, and it will be true of Sinner and Alcaraz, too. Being able to capture some of the goofiness and awkwardness of a player at the start of their career when they’re trying to figure out how to do international stardom was important to me.

Because we’re doing this at a company retreat, I was able to solicit some staffer-submitted questions before our interview. Kelsey was telling me at breakfast the other day how much she admires your writing on the sentence level. I think all of your coworkers and readers do. I was actually thinking back to when I interviewed Sabs for this series, and we talked about how they wrote figurative language—an octopus was the “reddish purple of a salted Japanese plum.” A strength of your writing, and I know something you prioritize, is descriptiveness, especially when it comes to a player’s style, how they play. What are the kinds of things you look for or notice when you’re trying to convey what a player plays like?

It’s funny that you bring up Sabs, because a lot of what I was intaking when I was writing was nature writing and art writing—things that try to evoke a visually compelling subject without assuming any prior familiarity with that thing. I think that can be a trap for sportswriters, who are like, My reader has been watching sports for forever. I don’t actually need to explain what this looks like. But it’s fun to strip it down and explain it to someone with no context going in. When I’m writing one of those passages, I’m trying to: One, just playfully evoke the experience of watching that player, so that could be things like temperament, but also their body language, the way they interact with their box, all these things that just won’t come through in the gamer or the recap of the match. They’re the in-the-moment experiential feelings of watching the player. And then two, in what ways do their playing style and their personality contrast or dovetail, or what’s the relationship between those two things?

With Carlos and Jannik, it’s quite coherent, because I think they both play tennis the way they are as people. But I think it’s a little more disparate with other players. It’s almost like I’m writing about an animal I find interesting: Here’s their habitat, their preferred court surface, here’s what they like to do on a tennis court, here’s what they don’t like, here’s how you beat them, here’s how they beat you, like an animal fact file.

You’re like the David Attenborough of tennis. I think about this a lot because I also write about a sport that’s more niche than the NBA or NFL, and that descriptive mode ends up being a good way of satisfying a broad range of readers. If you’re really familiar with the players already, you still find it valuable to have something articulated. And then if you’re not, you now get this really full sense of them.

That’s exactly how I feel. I wanted it to be a book that, for a longtime tennis fan, hopefully it helped to articulate some vague feelings. And then if you’re coming to it fresh, I hope it handholds you and helps you understand these interesting personalities and the dynamics on the tour.

The “how they play vs. how they are” point reminds me of a feeling of mine articulated in this book: the feeling that sportswriting is just taking this random blob of stuff and trying to shape into something and feeling really stupid about it sometimes. Were there any moments where you felt like, I’m maybe pushing this too far or trying to narrativize too much?

100 percent. There were times where I felt like I was pushing something too far, and I’d end up removing some of that, but what ended up being a good reality check was realizing even Jannik and Carlos view themselves in those super trope-ified ways. Carlos, you’d ask him what he envies about Jannik, and it really is I wish I was less up and down and wish I was so even-keeled and consistent, and you’d ask Jannik, and he’s like, I wish I had that spontaneity and the feel and creativity.

They’re the perfect foil for one another, and I found myself getting almost frustrated. Especially in tennis, there’s this frame of a rivalry being “fire and ice,” like Sampras and Agassi, Borg and McEnroe. Especially in the men’s game, that trope is really strong. And I’m like, Am I just doing another one of these? But then they simply played to the part, so faithfully, throughout the course of the season. One guy’s being the ice man while undergoing his secret doping scandal and the other guy’s reaching crazy high peaks but also flaming out early and smashing his racquet. I didn’t use those exact words, because I was deliberately trying to avoid that framing. I didn’t want someone to just read that sentence and check out, because it would be fair of them to do so. But I kept thinking, This is too perfect.

I often feel sportswriting is trying to capture a story that’s really only in these athletes’ heads and maybe even in their bodies, because sometimes they aren’t able to verbally articulate all this stuff in the moment. You feel a little silly trying to grasp at all the wisps and trying to tell a little story out of it. But when you collect enough data over the course of a season, it helps.

You have a good line about the “bell curve of sports commentary.” [“High-decibel talk-show shmucks say it’s all about who wants it more; middlebrow commentators like myself try to offer sober technical analyses; transcendent athletic geniuses say it’s all about who wants it more.”] Were you ever rooting for specific things to get the story you wanted or more interesting results?

For sure. One of the nice things about being able to write at Defector is we can retain some elements of conventional fandom while still doing our jobs, which I think is not true for a lot of sports journalists. I didn’t feel that around this book; what I felt instead was I wanted Jannik to kind of close the gap with Carlos. When I started putting the book proposal together at the end of 2023, Jannik was first making this leap, and I thought he was going to win a major the next year. Then it was one major to three majors; now it’s two to four; now it’s two to five; now it’s three to five, four to five. I keep thinking about wanting it to be on level terms.

It’s more fun to convince a reader of a rivalry when they are actually both beating each other. And it kind of sucks to, at the start of a tournament, feel like it’s a foregone conclusion, like this one guy’s going to win. Now at least we got One of these two guys is going to win.

Tennis has this great literary tradition, and I wonder what books—tennis or non-tennis—that you found helpful as you wrote.

I re-read [John McPhee’s book about one U.S. Open match between Arthur Ashe and Clark Graebner] Levels of the Game—obviously an amazing book. It can drive you insane when you think about the fact that he was able to sit down with these players and literally watch the match and pause it and talk to them about what they were thinking. Like, sure, would love to do that. Not a very 2025-feasible thing. I think what I was looking for was less reporting techniques and more structural stuff. People love that book because of how it weaves between real-time exposition about a tennis match and then these digressions into the players’ backstories. I knew my structure was going to be a little more conventional and chronological, but I think there’s something about the nimbleness with which he moves between those two frames, which I found compelling and tried to apply in the book.

In terms of non-sports stuff, I was reading Annie Dillard a lot—lovely, kind of trippy descriptions of the natural world. And then I was reading—almost an exercise in tedium, but beautiful in its own way—this book called The Peregrine by J.A. Baker. He just follows these two peregrine falcons that are in his area of somewhat rural England, and it’s like a daily log of their behavior from November to March. He’s describing two creatures very minutely over and over again, but can do it colorfully enough to sustain your interest. It’s a really inspiring bit of creativity under extreme constraints, where he’s basically describing the same few phenomena: Falcon’s diving, scouting the prey, it’s eating, it’s hanging out, it’s resting, it’s bathing, but he finds new ways to frame it, new metaphors, and you still want to keep reading.

I read a little John Berger. He wrote this book called Photocopies, which is a series of fairly disconnected vignettes taking place all over the world, mostly things he’s firsthand observed and it’s very good at scene-setting and establishing a sense of stakes in a very short amount of time. The last one was Janet Malcolm’s memoir, Still Pictures, which I really loved because she’s using photographs as a launching pad for telling the story of her childhood and early adulthood. It’s not a perfect analogue, but there are some comparisons you can draw between art criticism and sports writing in that you’re taking something that someone can just look at and take in directly in its entirety, but you’re trying to unpack it, add a bit more useful context, break it down, digest it. Technically it was useful for me to be reading stuff like that.

This brings me to our next staffer-submitted question, which is from Patrick. I don’t really understand the question. Possibly it’s some inside joke I’m not getting. Maybe it’s just a sincere and strange question. It’s whether you have thought about the other authors or books who will be next to you on a bookstore shelf.

Oh, wow.

Other “Na”s?

I never know how stuff gets classified these days. I hope I can be in the “Local Author” section of my local bookstore. That’s what I’m really pulling for. Because I think the sports section in that bookstore and many others is kind of relegated to a sort of sad, remote corner of it.

Maybe it’ll be a “Staff Pick” somewhere.

Oh, I would love that. We talk about this a lot: We’re frustrated when other sportswriters feel—it’s clear that they’re embarrassed to be writing about sports. And I’ve never felt that way, but I also don’t want my audience to be limited to people who already know about this sport. So I’d love for it to be just general interest. A “New Nonfiction” table would be great. I really deliberately tried to write it in a way that there would be access points for a longtime tennis fan and then people who don’t care about sports, but are interested in reading about personalities and high-stakes games. But I haven’t thought about my fellow “N” names. Can you think of any?

No, not really. That was a more insightful answer than I thought I was going to get from that question, honestly. I’ll wrap up with my final question. This year, conveniently, your thesis is holding strong. Sincaraz played, like, the best match ever at Roland-Garros—

[BARRY barges in and rudely interrupts our interview, babbling to us about something most likely of little importance.]

[We tell Barry to scram.]

—anyway, something you note about Carlos is his capacity to learn stuff really fast and evolve. Is there anything in the book that you look back on, even in the short span of time that’s passed, and feel differently about now or wish you could change?

Mostly it’s that I probably shouldn’t have hedged. In 2023 and 2024, Carlos was such a dominant player on grass without a great serve. And in 2025, he showed up on grass and was kind of servebotting his way through Queen’s [Club Championships, a grass-court tune-up tournament before Wimbledon]. Already this guy’s refined a really important aspect of his game in the three months since I put down my pen and stopped writing this book. Mostly I feel like it’s all happening way faster than I would have expected when I began to write the book. I’m grateful for them delivering on our wink-wink handshake deal: If you guys play well, you might even get to be featured in a book read by dozens of people.

On the “New Nonfiction” table.

On the “New Nonfiction” table.

Maybe.

A book that will maybe be on the “New Nonfiction” table at select New York City bookstores. I haven’t had time to sit back and distance myself from the story because it’s only been intensifying since I stopped writing. As the 2025 season has shown, I could have gone insane trying to keep up with every last development. In a dream world, maybe I could do a sequel in the middle of their careers, and then if we can still read books at that point, I’ll do one at the end of their careers.

Oh, actual last question: I thought it would be funny to feministly ask you how you’re balancing parenthood and a career.

It was a real gauntlet of a couple weeks where I was figuring out how to be a dad and also finishing the revisions of the book. I have an extremely tedious process with the revisions where I wrote the chapters longhand, then I typed them up, received edits, got them back and then I typed them all up from scratch. So I was kind of typing up the whole book while also sleep-deprived and changing a lot of poop diapers. It was really grueling, but it was almost nice where every time I was working on the book, I was excited to go back and hang out with the baby, and then there were moments where it was nice to have a bit of distance from the baby and be able to think about something outside of our family life for an hour here and there. They did kind of naturally complement each other.

It also just added an urgency to my hitting the deadlines, because I knew the baby was coming roughly around a certain date, and I needed to have it like 90 percent done. She helped me be more timely than I might otherwise have been.

Also it’s just made me a lot happier. I think it could have been a really grim series of staying up to 4 a.m. doing these revisions. There was a lot more smiling and laughter than there would have been otherwise. I think she might be a Jannik Sinner fan. She plays with a stuffed carrot.

Changeover is out from Gallery today. If you’re going to the U.S. Open on Aug. 25 or Aug. 26, come say hi! We’re setting up a bookstand on the boardwalk between the 7 train station and the tournament. Giri will be there selling and signing copies: 4:30 to 7:30 p.m. on Aug. 25, and 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. on Aug. 26. A collab between Defector and Astoria Bookshop.