Bill Anders First Saw The Earth

The Blue Marble showed the Earth in all its vitality, a living, changing thing. The Pale Blue Dot showed the Earth in all its cosmic insignificance. Before either of them, there was Earthrise. Taken by Bill Anders as he and his crewmates became the first to shed our planet’s gravity and orbit our moon, it was the first to do to a person what any great space photograph does, or really any great photograph period: change your perspective. Earth, for the first time, was over there. For it to be over there, humankind had to go out there. Other men were the first in space, the first on the moon, will be the first on Mars. Anders might have them all beat. He was the first to see our home as it truly is.

William Anders died Friday, and because he was an astronaut from the days when astronauts were test-pilot adrenaline freaks (though he, an Air Force man, went the nuclear engineering route), he did not die quietly in his bed. He died piloting his small plane, his Beechcraft T-34A plummeting into the water off the San Juan Islands in Washington, apparently while attempting a Split S. There is video of the fiery crash, and I don’t find it disturbing. Almost the opposite. There’s no good way to die, but for a man who led a longer, fuller life than most can dream of, and who spent much of it free and clear of the ground, I can imagine there are worse ways than while performing aerobatics in your own plane at the age of 90.

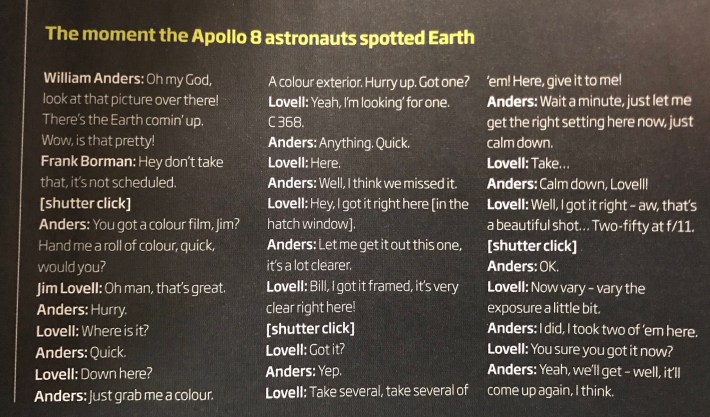

Anders, Frank Borman, and Jim Lovell spent less than a day in lunar gravity, making 10 orbits on Christmas Eve of 1968. Their main task was to observe the Moon, Apollo 8 preparing the way for Apollo 11’s landing the next summer. The Moon was dead—”The Moon is “essentially grey, no color, looks like plaster of Paris,” Lovell described it; “like a dirty beach” was Anders’s descriptor—but as the orbiter coasted, Anders spotted something blue and alive on the horizon:

Their excitement is palpable, even in a transcript; the recording conveys something even more pointed. They were seeing something no one had seen, from a place no one had been, and they—the most unflappable men our country could produce—were awed.

Earth, from afar, coming up over the rim of the Moon. The terminator, cleaving Africa; the Americas sheathed in cloud; the white of Antartica just visible (at left in the popular version of the photo, used above, which is rotated 90 degrees from the original). The planet was not actually “rising,” in the way that the rotation of the Earth makes the Sun and Moon rise. Because one side of the Moon is tidally locked to Earth, an observer would never see the planet rise unless they were traveling at speed, as Apollo 8 was. But Earthrise it was dubbed; one fits old paradigms to new perspectives to make them comprehensible.

But sometimes the new perspective is so jarring, it forcibly ejects old ways of thinking. It did for Anders. “Borders that once rendered division vanished,” he recalled. In another instance, he remembered thinking, “This is the only home we have and yet we’re busy shooting at each other?” We did not stop shooting at each other, of course, and have not. But it sure looks a whole lot stupider from that distance. Time Magazine put the photo on its final cover of that bloody 1968, with the one-word caption—a hope, really—of “Dawn.”

Apollo 8 is also famous for its astronauts’ Christmas Eve Message, in which they took turns reading from the Book of Genesis for a television broadcast. It resounds because of its poetry, but Anders had already had his faith shaken by the sight of true earthly glory. “It really undercut my religious beliefs,” he said. “The idea that things rotate around the pope and up there is a big supercomputer wondering whether Billy was a good boy yesterday? It doesn’t make any sense.”

Anders, after serving as backup crew for Apollo 11, retired from NASA to serve as an aerospace executive in both the public and private sectors, before retiring to Washington State, where he and his wife Valerie founded a museum of flight. Earthrise eventually took on a life of its own, serving as a symbol of the nascent environmental movement. We could see, now, what we hoped to protect. The photograph surely inspired some to be astronauts and scientists, others to be poets. We all see something in there, but perhaps something different for each of us—something that speaks to what we value most. Bill Anders saw it all, and saw it first. In 2018, he wrote an essay to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Earthrise. “We came all this way to explore the moon, and the most important thing is that we discovered the Earth.”