A Small And Beautiful Seahorse Reveals An Even Smaller And Reclusive Worm

Years ago, as a student at the University of the Ryukyus in in Okinawa, Japan, Ai Takahata was researching the color patterns of a seahorse about the size of a shelled peanut. The pygmy seahorse Hippocampus bargibanti lives only on knobbly, branched corals called gorgonian sea-fans, where its own, equally lumpish body is perfectly camouflaged. When Takahata cut off a branch of the seahorse’s coral, a handful of worms spilled out.

She brought the worms to Chloé Julie Loïs Fourreau, a PhD student in the same lab at the university, who studies worms. “At that time I didn’t even know about this species and wasn’t looking for them,” Fourreau wrote in an email. But when Fourreau looked into the literature, she identified them as Haplosyllis anthogorgicola, a species of polychaete worm that was first described in 1956 and then never recorded again. The researchers had unwittingly rediscovered a long-lost species of a tiny, nearly transparent worm about as long as a green lentil. Their paper on this rediscovery, “The Trojan seahorse,” was published recently in Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Although the worm had not been recorded for more than half a century, it is unclear if anyone had been looking for it. The oceans are full of tiny, translucent, and easily overlooked worms of varying species. H. anthogorgicola worms are not just tiny, but they also live inside burrows in the coral, making them even more difficult to detect. And if their coral home is collected, the worms leap out of their burrows soon after. “The worms are quite sensitive,” Fourreau said, adding that Takahata only noticed the worms because she saved the surrounding seawater. Once the worms leave their dens, “they are very easy to see as they are so numerous,” Fourreau said.

Time passed, and Fourreau worked on her other projects. She was nearing the end of a trip diving in the turquoise waters off Kashiwajima in southern Japan when she saw a dive shop advertising the pygmy seahorses as local attractions of the reef. If Takahata had found the worms, Fourreau reasoned, maybe she could too. She took a boat to the seahorses’ corals, which sprouted about 80 feet below the surface, and broke off a branch. “Lo and behold the worms were there!” Fourreau said.

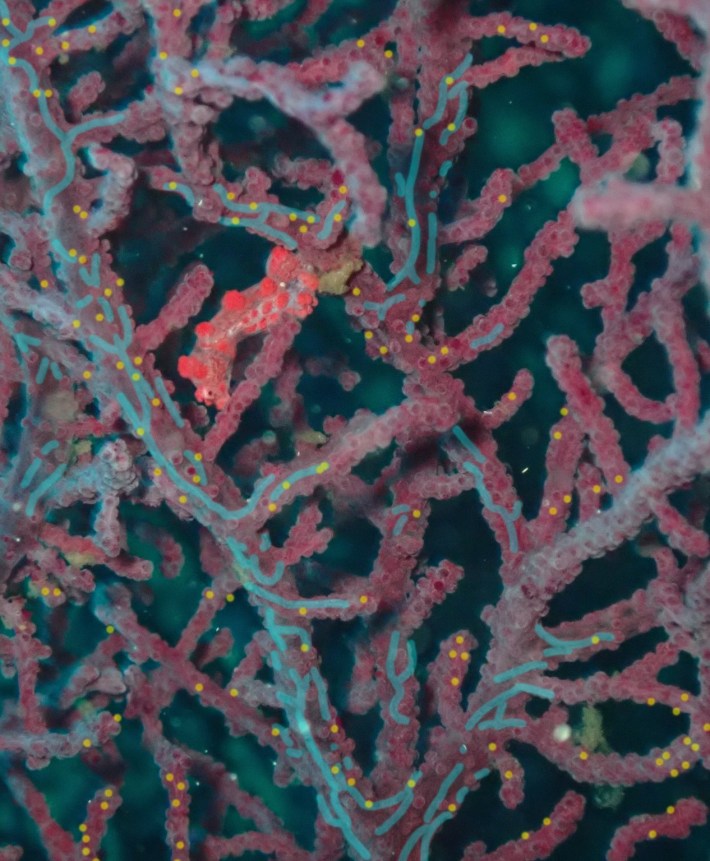

When Fourreau sorted through the photos she’d taken of the seahorses and the coral, she spied traces of the worms: their signature burrows streaked the coral branches like rivulets. She realized any photos taken of the seahorses—which are dive photographers’ darlings— might have inadvertently captured evidence of the worm. When Fourreau searched for the seahorses on the species-identification app iNaturalist, she saw the worms’ burrows lurking in the background. She could even spot the tiny, transparent worms in some of the pictures. As it turns out, people had been documenting the worm for years.

But the iNaturalist photos didn’t only reveal the worm’s general presence, or, in one case, precise GPS coordinates. They also offered snapshots of the worm’s behavior—rare insight into a little-observed species. “All of our research is based on the little we see of the worms when they are partly outside, but they seem to be inside most off the time,” Fourreau said. “What do they do?” The worm’s burrows connected into networks called galleries, which seem to allow the worms to travel throughout the colony and switch up their burrows. “Could they be fighting to occupy certain burrows, or somehow cooperate?” Fourreau asked.

The worms, the corals, and the seahorses strike a delicate balance as roommates, and the researchers are still trying to understand the trade-offs of this living arrangement. “Clearly, the coral is benefiting both the worms and the seahorse by providing them this wonderful habitat,” Fourreau said. Both the seahorses and the worms have evolved alongside the coral, changing their bodies to camouflage in its colors or burrow within its branches.

Researchers studying similar worms previously suggested the worms steal food from the coral. Their burrows appear to connect coral polyps, which are the individual animals that comprise a coral colony and can open or close. Open polyps eat by grabbing drifting food with their mouthful of tentacles. So Fourreau expected the worms would hang around open polyps to maximize stealing food. But in reality, the worms lingered around closed polyps. This led Fourreau to suspect the worms are not stealing their food but eating the coral’s leftovers—hoovering up whatever scraps are stuck to the tentacles and cleaning the coral in the process.

Fourreau also wants to test a hypothesis that the seahorses may be eating the worms, based on some iNaturalist photos that appear to capture a worm that is about to get eaten. Scientists do not know much about their diet, and the worms would certainly be convenient prey. “There are so many worms available everywhere on the coral,” she said. For the worms’ part, they seem suspicious of the seahorses. Photos captured them emerging from their burrows in various intimidating stances and even crawling on the seahorses. The researchers suspect the worms may be doing this to protect their host, defend their territory, or keep themselves from being eaten, although this would have to be confirmed by deeper investigation, Fourreau added.

Although the worms often poked their heads out of their burrows, they were rarely seen fully outside the coral. But a few iNaturalist photos captured the worm clinging to the seahorse itself, which the researchers can’t definitely explain. The researchers speculate the worms could be “mobbing” the seahorse to defend themselves. Or “maybe the pygmy seahorse is so good at camouflaging that it is fooling the worms too,” Fourreau said.

In Fourreau’s eyes, the research shines a light on the unexpected complexity of worms—how their relationships to their hosts, other species, and even other worms may be more intricate than scientists assumed. This complex network of interactions underscores how scientists should study a species alongside its neighbors, symbiotic or otherwise. “We will be able to better understand all of them by considering them together,” she said.

Another takeaway from the research may be a lesson for anyone else working with a little-loved, often-overlooked animal. Fourreau and her colleagues study marine invertebrates, which receive far less public attention and resources than a charismatic oceanic celebrity such as a seahorse. “I think that the idea that we can sometimes refunnel information available on a species with lots of data, to learn about a lesser-known species, can be applied to so many things,” she said. So if you find yourself uploading a photo to iNaturalist, remember to zoom in for any lurkers in the background. Maybe you, too, can rediscover a worm.